Across the expansive rooms of Berlin’s CFA gallery, Archie Rand’s paintings are dreamlike cynosures demanding exacting focus on the most minuscule and seemingly irrelevant details. Two walls, for example, just as you enter the gallery, are hung with modestly-sized works (30 in total)—all invoking a surreal medley of improbable collisions of objects and events, and all of which are untitled. As the exhibition branches off to the back of the gallery, the 12 works the show is titled after, Sons, have a strangely magisterial quality about them—perhaps due to the fact that they mingle disturbingly militaristic themes with a cartoon fantasia color palette. Although they’re different bodies of work, the fact that Rand’s untitled pieces are being shown alongside his paintings made after Francisco de Zurbarán’s Jacob and His Twelve Sons suggests some kind of overlap in methodology, if not theme.

Archie Rand, Untitled Series, 2024, exhibition view, CFA Berlin © CFA Gallery.

Viewing these works, it’s important to note the dreamlike ambience of each painting. The uncanny landscapes of heraldic color, and the way each image seems to spatially unmap and delocalize itself, uprooting the work from anything like a recognizable place. This dislocation is achieved by way of the very gestures and pictorial strategies that ordinarily make representations of place possible. For all the airs of absurdism and comedy infusing these works, the viewer is left in the peculiar position of being a spectator’s spectator. Cut off from time as much as place, de jure if not de facto, one feels softly assaulted by these carnivalesque images that are always happening in medias res.

In the 12 paintings comprising Sons (each, following Zurbarán’s lead, titled after one of Jacob’s Biblical sons), the sense of whimsy and pathos derives largely from how foreign the imagery feels. As poet and art critic Barry Schwabsky points out in his excellent text accompanying the exhibition, Rand’s imagination filters comic books, pulp fiction, and even westerns from a time when these kinds of things were more integral to the collective consciousness of American pop culture.

Having been more or less submerged by digital media or films that endlessly pay homage to them—from Instagram pages devoted to monster comics to movies by Quentin Tarantino—Rand’s reworking of Zurbarán’s imagery in terms of mid-20th-century nostalgia smacks of what Freud would call “the return of the repressed.”

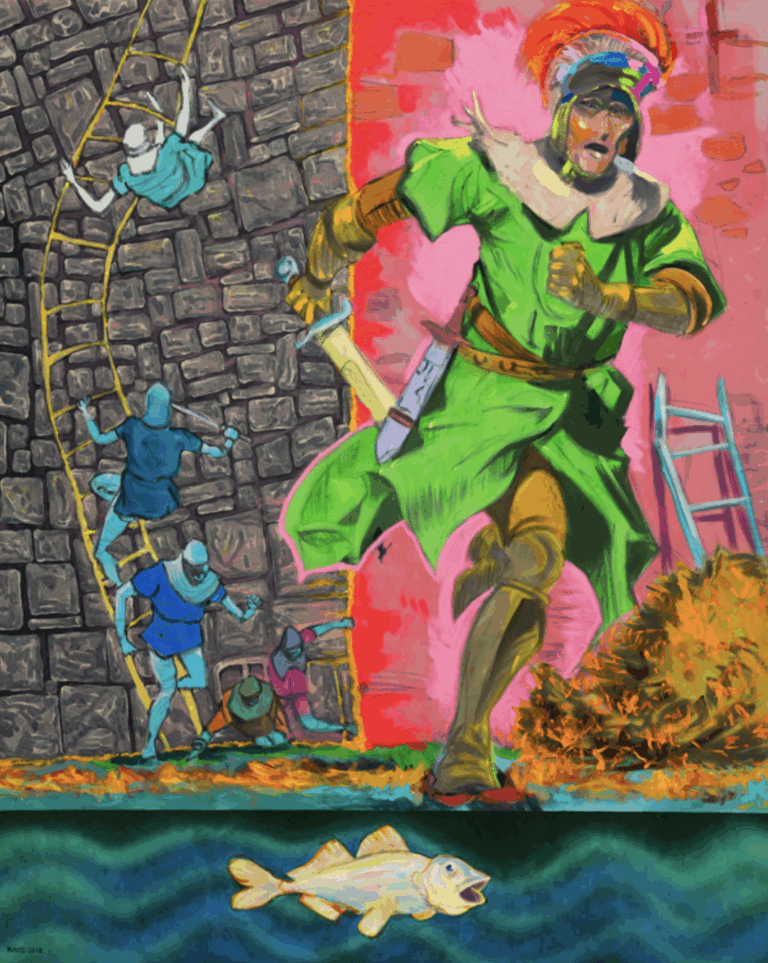

Archie Rand, Zebulon, 2019 © Courtesy of the artist

Soldered to the Biblical armature Rand drapes his ludic imagery across, this return—which leans on heroism generally—takes on a bathetic aura in light of the absolutely hopeless situations many of the figures in Rand’s paintings seem to discover themselves in. In Zebulon (2019), in particular, horror abounds as a medieval soldier (presumably a stand-in for Zebulon) flees the walls of a castle, while other soldiers behind him are visibly routed from their onslaught. Even the fish at the bottom of the canvas, which one might think would otherwise be symbolic and decorative, seems alarmed by the sheer declivity the general state of things has snowballed into.

Rand’s method of painting here is a way of redistributing imagery that feels strange in itself. If these canvases could talk, if we could overhear them thinking, they would probably be horrified by their own strangeness. And yet the works are not without a decidedly ludological overtone—that is, a logic borrowed from games, from systems governed by rules the viewer can intuit but never fully access. This is so if only because Rand refuses to let the viewer in completely. Standing before each of Rand’s Sons, everything transpires as though the viewer were witnessing the clamor of someone else’s dreams, shot through with all the warmth and intimacy that dreams recall upon awaking. As an outsider to this state of consciousness, as though gripped from within, he or she remains a sort of passive bystander, unlocking the doors to a universe that is only partially familiar.

Archie Rand, Issachar, 2019 © Courtesy of the artist

Yet what distinguishes these works from, say, Magritte, is how period-piece nostalgia (comics, westerns, anime) readily elides into a sense of temporality—of activities unfolding over time—suggested by the partitionings Rand imposes on his pictures. Where Magritte might use a bowler hat or a green apple as a clever form of misdirection, Rand’s allusions to bygone media and the messages or tropes they once gave rise to function as an exposition of the sounding principle media itself brings to bear upon our lives. In this sense, “media” (in its univocal sense) is understood not as content but as condition. From the theme song to Super Mario Bros. to epoch-making moments of reportage, how something appears—how it was mediated—is just as important as the message or content it carries.

Archie Rand, Simeon, 2019 © Courtesy of the artist

From this, the weird perspectives at play in a painting like Simeon—particularly in the plague doctor and the boy gripping a stick and some other mysterious object in his ghostly arthritic hand—can allude to times quite apart from the experience of time synthesized in the painting itself. Simeon thematizes a medley of battles, both martial and survivalist, that have appeared across our Western historical timelines. It also offers a way of revisiting, restaging, or reimagining—especially with regard to how images constellate ideas—how Zurbarán’s vision of Jacob and His Twelve Sons might appear today, at a moment when Judaism, often discussed through the lens of Zionism, is widely invoked but rarely understood in its historical or theological complexity.