When I arrived at Charlie Stein’s apartment, the evening was already settling in. A mellow soundtrack played in the background, and the warm scent of an Acqua di Parma candle filled the space. Dressed in chic loungewear, her signature hairstyle perfectly intact, Stein exuded the understated cool that defines both her presence and her work. As she handed me a cup of her favourite tea—a soothing blend of liquorice, fennel, ginger, and thyme—I took in the surroundings. The space felt like an extension of her practice: sleek yet playful, with hues of pink and purple weaving through the modern decor.

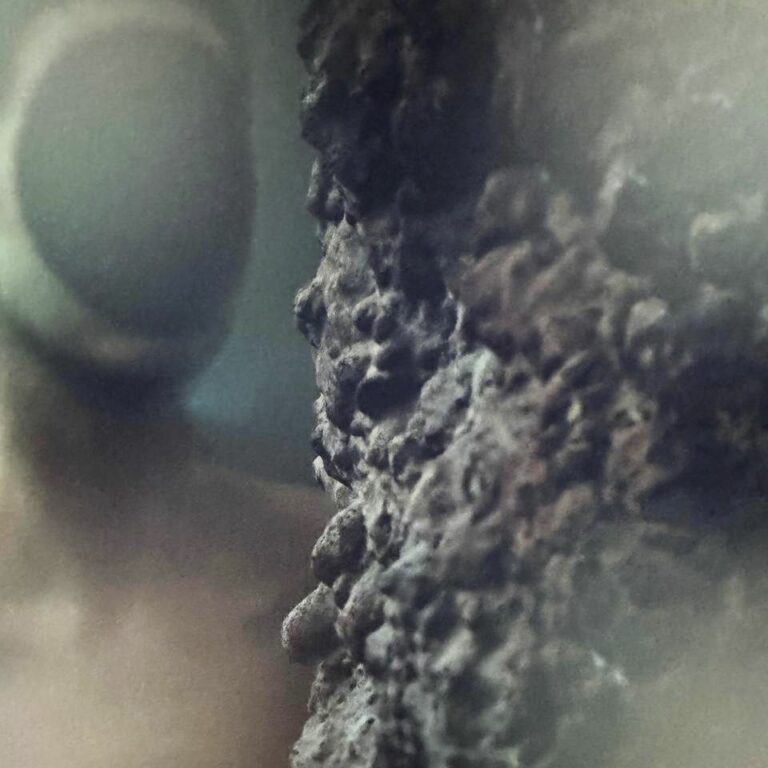

With my tea in hand, she led me to the back of her apartment, where her studio is located. “I have to apologize that I haven’t made it pretty—I was so tired after the photo shoot,” she said. I found this amusing because, to me, it looked great. The contrast to the rest of her home was striking. Gone was the warm, ambient glow that filled her living quarters; instead, a harsh, clinical white light flooded the space, designed for functionality rather than comfort. But somehow, the intensity suited the paintings on the walls—shiny latex bodies clutching syringes, glossy black and silvery pink puffer jackets, polished black lucky cats. The studio felt raw and in tune with her work.

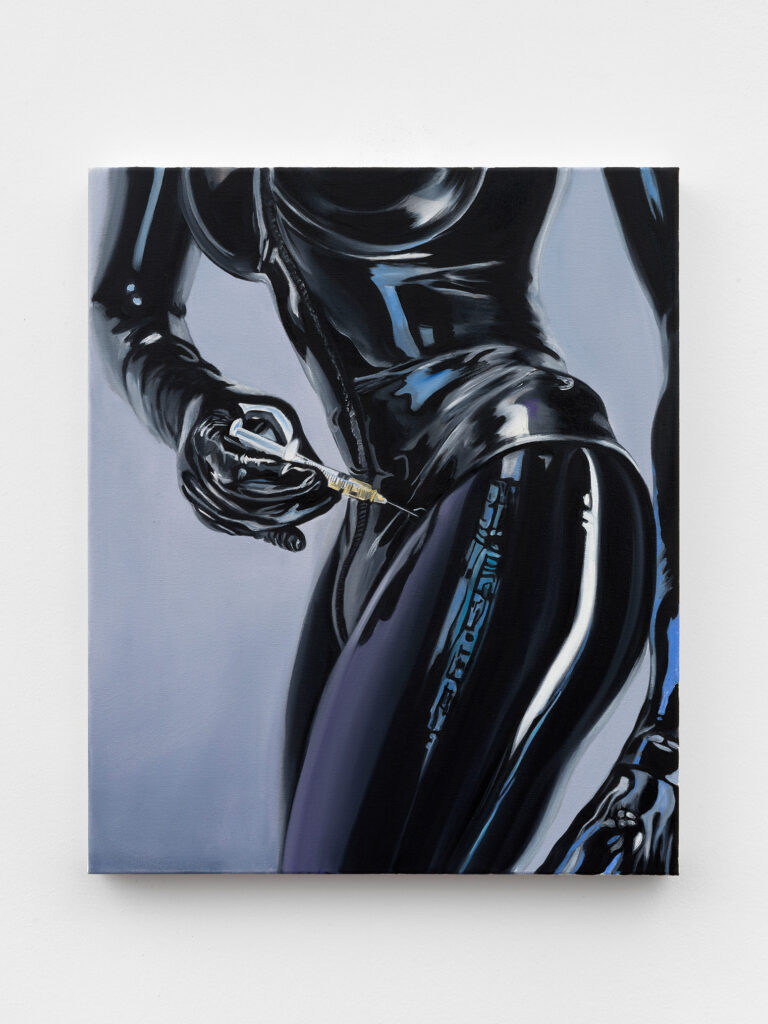

Charlie and I had planned our studio visit on short notice as the paintings that hung before us were just days off from being shipped to London for her next show with Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery at their Wandsworth location. The series is made up predominantly of womanly latex figures with syringes, either holding them or injecting them into themselves at various spots across the body. Fertility treatment and artificial insemination are at the core of the series, a topic which I’m told is deeply personal to the artist. “I thought it’s really interesting because [fertility treatment] is kind of like all the hormonal responses that you have when you’re having sex, but it’s completely medicalized,” she says. “I thought there is something so weird about that, and I think that’s why the fetish surface matches it so well.”

One of Charlie’s main intentions with her work is to lure people into the viewing experience while simultaneously keeping them slightly on edge. “I wanted to have [the paintings] enticing as if they were talking about sex,” she says, which on first glance is an easy reading to make of a material with such sexual connotations. “But at the same time, it’s the opposite of having sex. It’s like inserting some awful movement into your body.” She chuckles for a moment before adding, “but I guess you also need to be a little bit afraid of syringes to be a part of that.”

© Studio Charlie Stein, Thesmophoria (Phase VI), 2024. Foto: Roman März (VG Bildkunst)

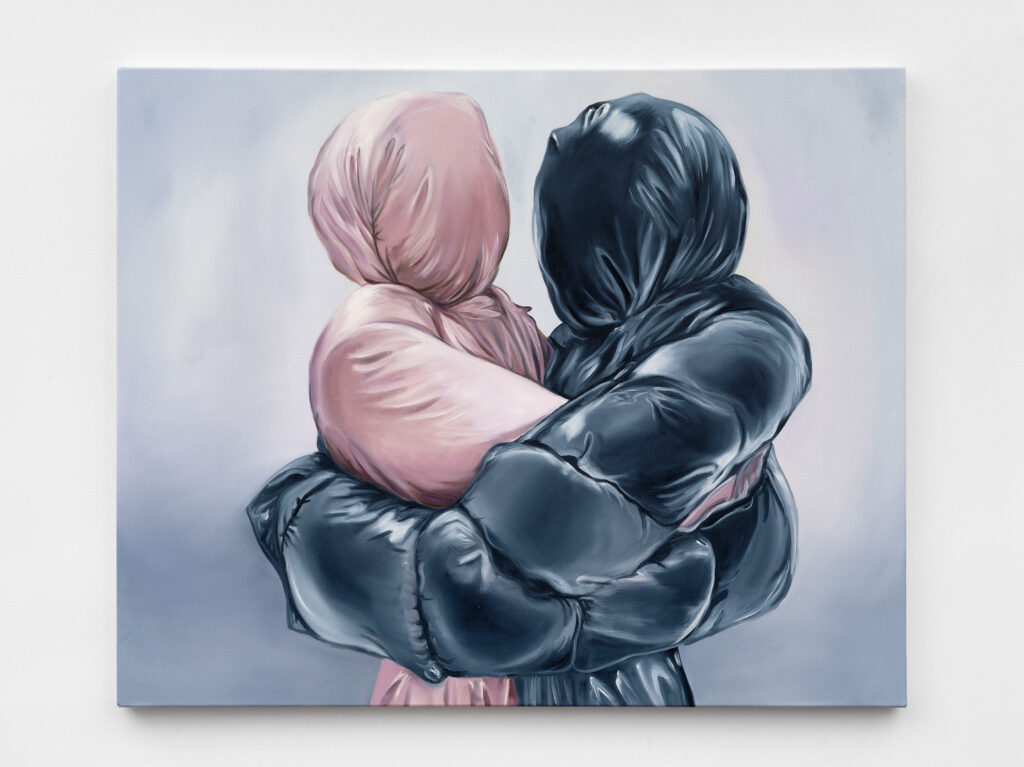

The series also includes figures locked in tight embraces, wrapped in oversized pink or black puffer jackets with their faces completely concealed in a way that immediately brings to mind René Magritte’s The Lovers. While the gesture suggests intimacy, the obscured faces introduce an unsettling sense of suffocation. “It’s all about obscuring the figure, which is a bit weird because other works I’ve done before, they had big eyes and they were kind of in your face, almost like manga characters in anime,” she says.

Curious about this shift in style, I asked her to dig out an old canvas. She pulled out a painting from Unimate, a past series where female robots with wide, doting eyes locked onto the viewer. The robots were named after a 1960s robotic arm from General Motors, and represented a kind of feminist take on a dystopian future. “This was before AI, so it’s kind of freaky,” she laughs. “They’re smoking, in Paris, and abandoning their chores and real life.”

Painting wasn’t always Stein’s focus. She started out instead by studying conceptual art. Leading me out of the studio and back into her living space, she rummages through a cupboard, searching for a model of an old sculptural piece. When she finds it, she pulls out a shoebox-sized version—an endearing miniature, each tiny element like pieces in a dollhouse. “It’s a playground where everything is safe,” she says. “I have a slide that’s on a zero-degree angle, just flat like it had given up. And I decided to paint it white because I thought that was very soft and minimal.”

She scrolled through her phone, showing me photos of the full-scale version—an installation that looked like the most dejected playground imaginable. All handmade, she tells me, though always a nightmare to set up. Still, the piece made its way into three exhibitions: a summer show at art school, a museum, and a biennial—an impressive trajectory for such an early stage in her career. But dazzling people was never the point. “I didn’t want to make work that would just impress people. I also wanted to make work that’s personal,” she says.

© Studio Charlie Stein, Virtually Yours (Perfect Lovers), 2024. Foto: Roman März (VG Bildkunst)

Her stint in conceptual art didn’t last long. As graduation neared, she found herself drawn more and more to painting, discovering that it was the medium where she could access something personal. She told me about how an art world contact also once said, “you know, when you graduate, that’s the shit you have to do for the rest of your life.” So, painting became the shit she would do.

Her graduation show marked what she described as her “coming of age with painting”—a massive project titled Study for a Museum Display. Through months of research and experimentation, she reworked the interior of the Villa Merkel in Esslingen as a riff on the old French salons—traditionally very masculine environments. She wanted to parody that history, creating a show that mimicked “some male genius.” To do this, she framed her paintings in gold or heavy frames and covered the walls with patterned wallpaper—which, upon closer look, was actually a kaleidoscopic print of her own face. It was like her way of playing with art history while asserting her own voice within it.

The paintings in the show established the beginning of her portraits—here, distorted faces were created by layering Snapchat filters on top of each other, resulting in bizarre, almost grotesque images. “People were really weirded out by them,” she says, laughing. But looking back, she’s immensely proud of what she created. “I had really thought this project out to the maximum because I wanted to have the license to paint after this,” she reflects. “I was really happy with that show. And that’s how I started painting and then I didn’t stop.”

As our conversation wound down, Charlie turned her attention to what lay ahead. She pulled out miniature models of each of the galleries she was set to exhibit at, carefully holding them up for me like pieces in a set design. Pointing to each space, she walked me through her plans—how the paintings would be arranged, how the visitors would interact with the space, how the atmosphere of each show would take shape. With upcoming exhibitions at Kristin Hjellegjerde, Kunstverein Schorndorf, and Kunsthalle 2 in Mallorca, she had a packed schedule ahead.

Heading out—me off to whatever opening was happening that night, Charlie settling in for a well-deserved night off—I found myself grateful to have caught her and her work before they moved on to the next stop. It’s easy to forget the feeling of being truly engaged with an artist and their practice, that rare spark when something really hits. But Charlie’s work did just that for me. Even now, writing about it, I feel that same excitement—for what she’s made and for whatever will come next.

© Studio Charlie Stein, Kitty with Teeth and Pills (Still Life), 2024. Foto: Roman März (VG Bildkunst)