Naama Rahamim: Welcome Linn, it is a pleasure having you here. I wanted to meet you today to talk about some of the projects you have worked on over the last years. Let us start with the topics you are busy with. In many of your projects, you deal with topics like love and loss as well as memories that you might lose. It feels like a diary, tell me about it.

Linn Fischer: I think you already mentioned the key word: „diary“. I grew up in a home where my parents kept diaries. Both of them had a diary in their first language from a very young age on. It was very important for me to understand myself through writing, documenting, and presenting things. Words have always been the basis of my creations and a way of expressing myself, long before I saw myself studying graphic design. Another important word for me is „longing“ since I love the feeling of it. After the stage of loss comes the stage of longing.

Together with that loss, there has always been a longing for parallel lives, for lives that could have been mine, for lives that maybe once were or now seem like utopias. One example is the life I had in the kibbutz which I left when I was young. From a grown-up perspective today, life in the kibbutz does not look like I remember it anymore. Another example is the longing I had for my father. He travelled occupationally to distant countries where I could have joined him but never did.

Naama Rahamim: Through your art, you preserve memories as they are, but more than that, you also create parallel worlds for yourself, turning tragedy into something romantic or utopian.

Linn Fischer: Exactly, and it is all imbued with romanticism. Pain often goes through a process of romanticization for me, because it is my way of reconciling a harsh experience with something poetic or comforting. Coming from a place of pain and longing, there is a desire to create something imaginary in order to manage living in that long-wished utopia. But it always remains at the level of utopia. The fact that it cannot materialise is what keeps it romantic. After all, if it did materialise it might not be what it seems.

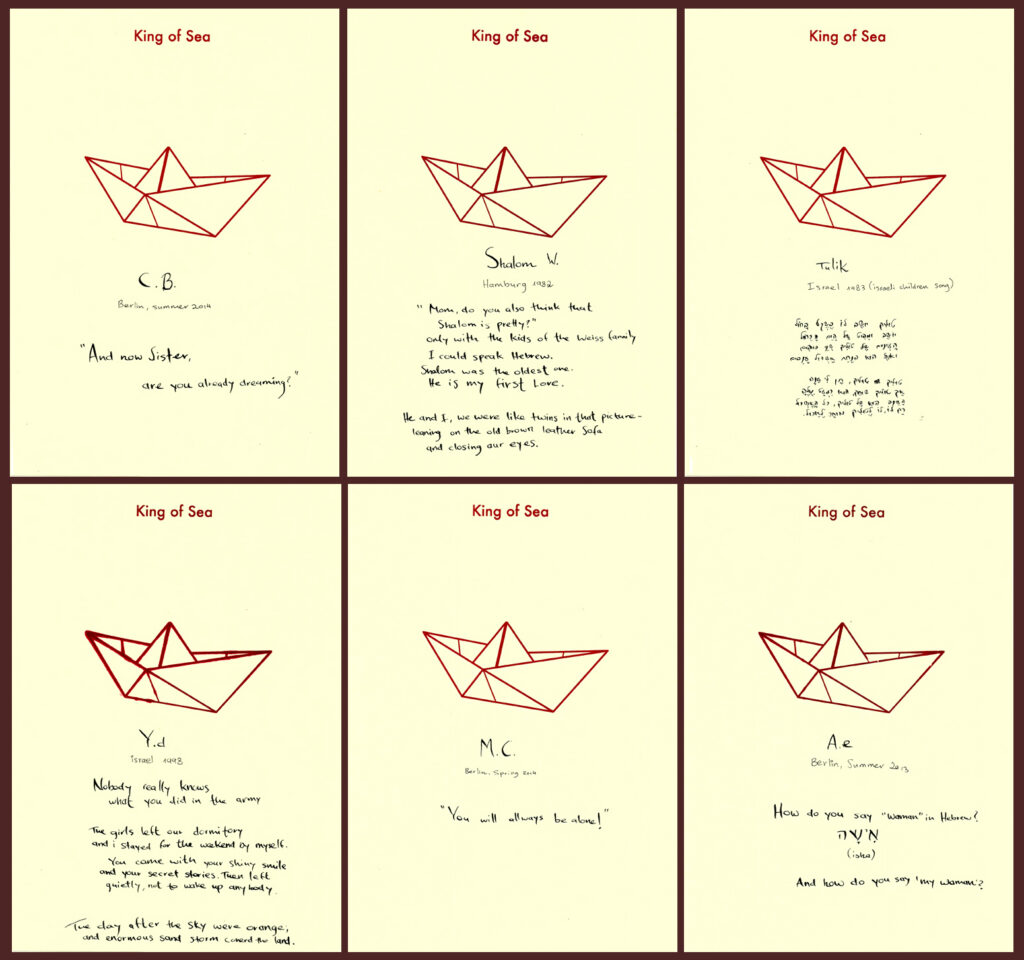

The work King of Sea is about love: The love I’m trying to capture, and many tiny moments of love that I’ve had in my life, told in little excerpts and words. Most of these moments are positive, but in the end, none of these beautiful memories is comparable to the experience of the absent father. King of Sea includes 50 different expressions of love. The diversity of love includes the somewhat sad story that my great love was not there. My great love is the one that is not romantic anymore. It is the one that remains simply because it is romantic – only that it does not exist or that it is going away or that it’s over.

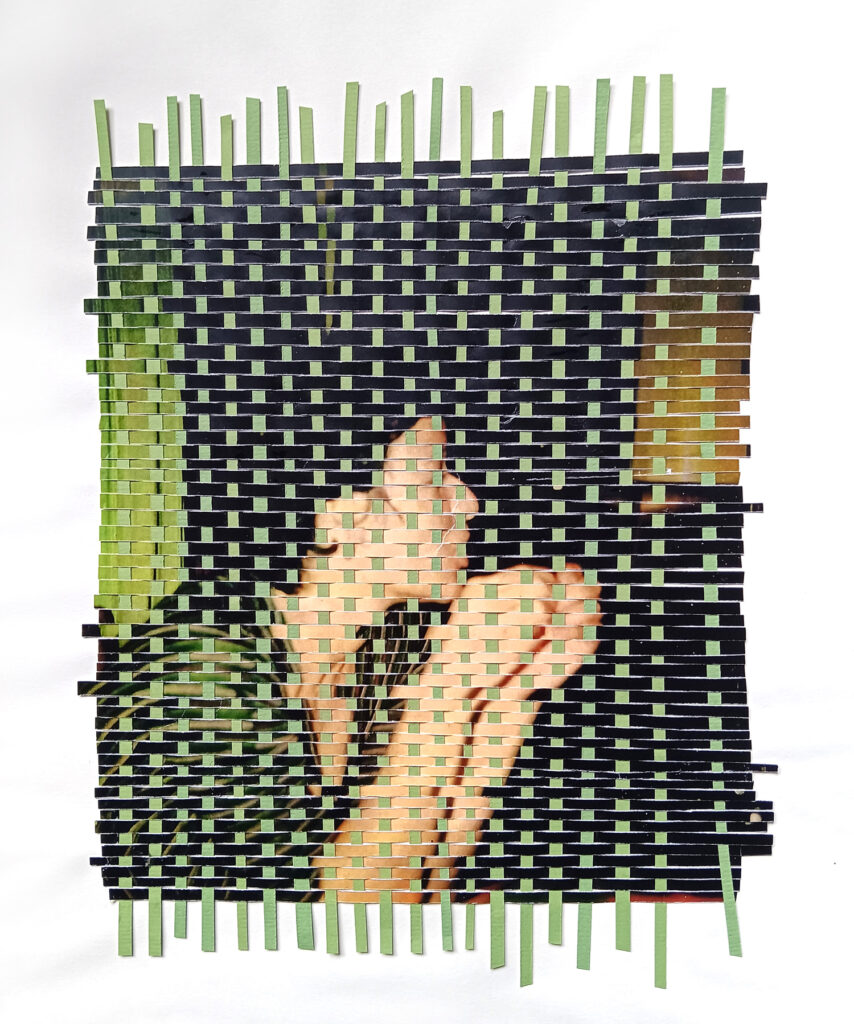

Naama Rahamim: In your work, you seem to play with conflicting emotions. In the series When I Will Recover (2015), you deal with serious and painful subjects like breast cancer in a way that some experience as joyful or even funny. How do contradictions help you to express yourself?

Linn Fischer: There is something about the contradiction that brings out the pathos. In the stories themselves, in the romance, there is a lot of pathos or something that could even be perceived as cheesy. To talk about pain, to talk about loss, and to talk about cancer – what else can you say about cancer that has not been said already? For me, there is something in the contradiction that brings out a bit of the sting. I created the series as part of the magazine RUW that I was involved in during those years. The result was 50 different pages of sentences about things I wanted to do after I recovered. The title of the magazine Nach dem Danach („After the After“) suited my situation.

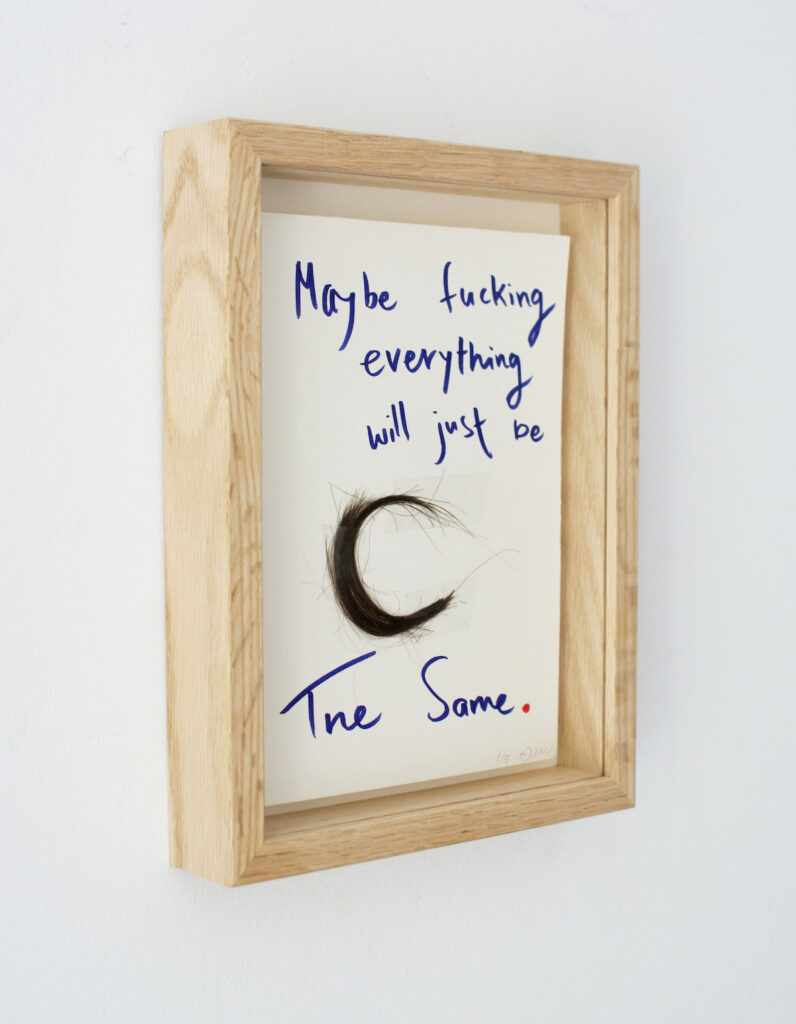

I was in the middle of chemotherapy, bald, exhausted in my bubble, and no longer connected to the world. It was important for me to do something despite the fatigue, and try to create something from a not-easy place. I wanted to expose my pain while hiding it with humour or with inhibition. On the one hand, there is a lot of pain and danger in this work. The question of what is going to happen in the end is constantly present. There is hair being cut off in an almost violent way. But on the other hand, there is a certain optimism, and alongside the optimism, there is a kind of indifference. One of the sentences I wrote was „Maybe everything will fucking be the same“, because I really wished for a sudden light after the cancer. In the very same moment I knew that there was a chance that I would have to start all over again.

Something in the contradiction allows me to take things a bit easier and to connect them more easily. It is less fun to see someone crying, it is more fun to see someone who might shed a tear but still manages to laugh at themself.

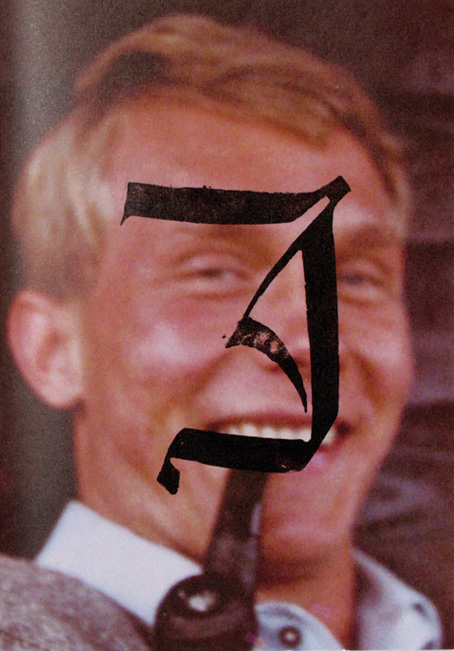

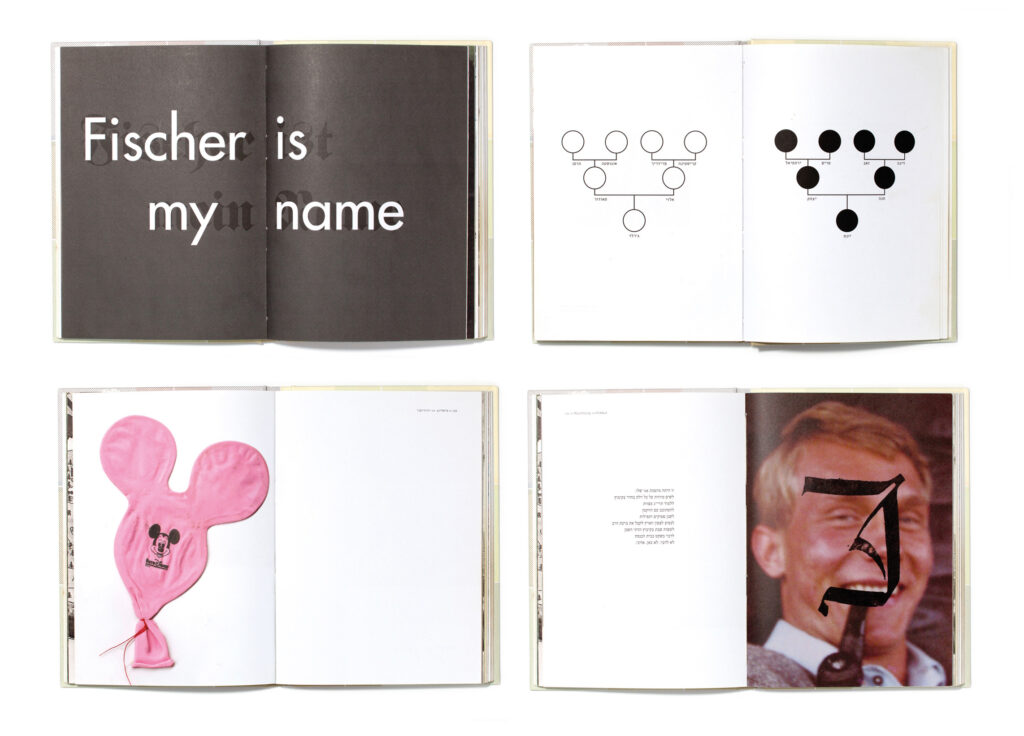

From the book Mischling (2019)

Naama Rahamim: In your final project at Shenkar (2009), you wrote an autobiographical book called Mischling in which you reflect on your identity as a child of a Jewish-Israeli mother and a non-Jewish German father. Could you tell me about it?

Linn Fischer: Mischling is a book that tells the story of what it is like to live in a bi-cultural family with a cultural and historical conflict in the background. Particularly, what it means to live in a family that is half German and half Jewish. The book talks about longing as well. Although I took a subject that has something universal in it, personally, it is a book that longs again for the kibbutz, for my family and for my parents. All these issues of German-Israeli relations and my German-Jewish identity, about the Germany I did not have and the Israel I always wanted, has formed into an interest which constantly haunted me. I was always dealing with it while searching for projects addressing this issue to understand more about it.

Mischling deals with the question of belonging. When I was in Germany as a child, I did not exactly feel that I belonged there. Then, in the kibbutz, I was dealing with the same problem. Having a foreign father always meant to live with a suitcase in the attic since I had a constant feeling that we were about to leave soon. The absence of belonging creates a feeling of longing. It is the same feeling I talked about earlier: This impression that I belong to another world – which is my world – has always comforted me. The book was one of the reasons I moved to Berlin. The other reason was my father who lived in Hamburg at that time.

From the notebook Long-term memory (2023)

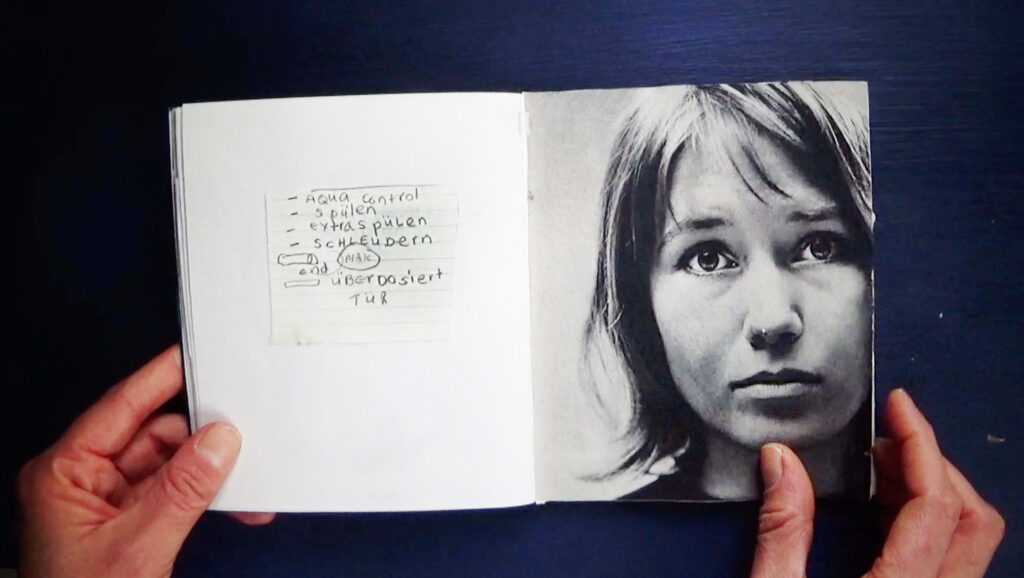

Naama Rahamim: In the notebook of Long-Term Memory (2023), you focused on the process of separating from your mother, who had died. In this process you found yourself working mainly with text again.

Linn Fischer: I made this notebook for an exhibition as part of the i_seeeeeeee project. Each artist was given an empty notebook with 36 pages and 30 days to fill it with artwork or artistic content they wanted to communicate. I wanted to work with my mother’s texts because she was a person of words. She wrote a lot, so I wanted to integrate her words. The rest of the work I have done about her is mainly visual.. Making this notebook felt like a kind of vacuum. Maybe one could say there is a playfulness in the book. I made this one technical choice of taking words and images and then I only framed certain kinds of images. That is how I work. I love the fact that there are frameworks; it gives me freedom. The limitations force me to invent something new, and in this work, I chose a very specific imagery from a very old book of engravings.

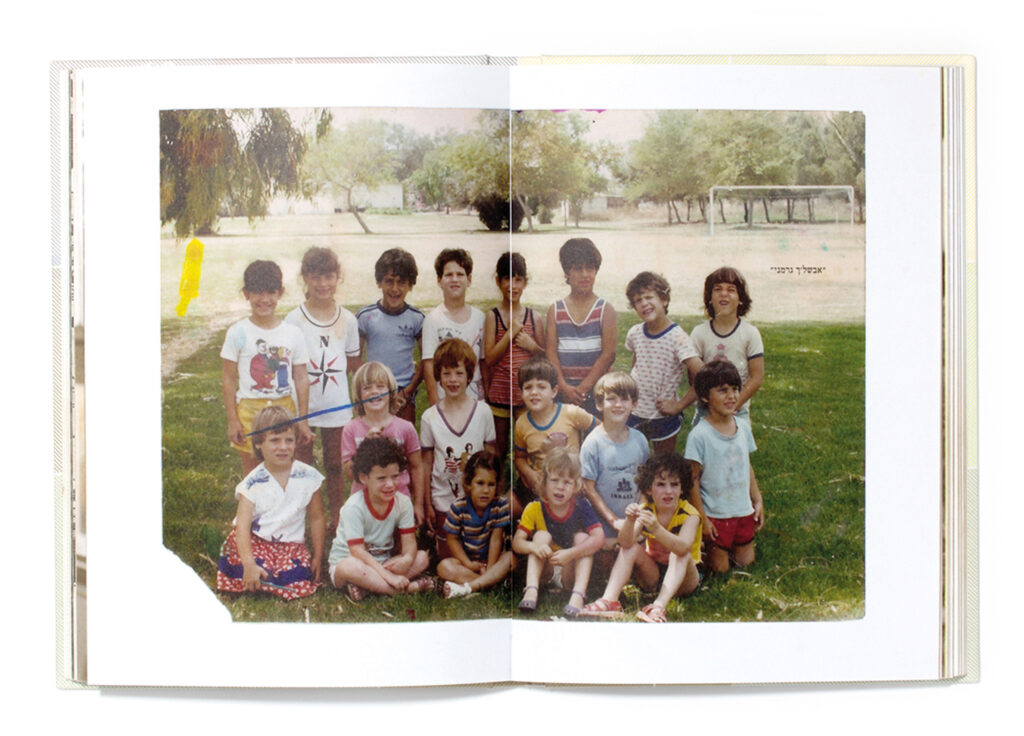

From the book Mischling (2019)

Naama Rahamim: You mentioned the kibbutz where you grew up, Nahal Oz, a place that became a heavy target by Hamas on the 7th of October. Do you feel that you have lost this place twice, once as a child who left, and once as an adult?

Linn Fischer: I came to the kibbutz from Germany with my parents at the age of four and stayed there until I was fourteen. In the kibbutz I was living with a sense of community, where all the adults raise you, where you know all the children in every possible aspect, whether it is in the kindergarten, whether it is in the communal dining room. It always felt like one big family, and leaving that was a moral and emotional crisis for me. At that time I also sensed that I was beginning to lose something within my family structure. My father went back to the sea at the same time, so my whole little world fell apart. When we were growing up in the kibbutz in the 80s, it was very quiet, there was no serious political threat. There wasn’t even a border. The links between the kibbutz and Gaza were very good. But since 7th of October many things have changed. Suddenly all the memories and beautiful spaces went up in flames, the security shattered and the loss became real. Suddenly it became everyone’s loss, not just mine. What I had felt before intensified and turned from utopian to sad. My personal longing turned into a collective catastrophe. It was so sudden, nobody expected it. Sometimes I feel that it is not even right to cry about it because it confirms that it really happened. I can say that I suddenly did not feel alone in my longing for the place itself. Many friends from the kibbutz group came together and wanted to meet, and suddenly I was part of them again after many years of no contact. But, to be honest, I would have preferred the place to still be there and for me to be able to visit it.

Naama Rahamim: Linn, thank you.

A very personal interview: Art agent Naama Rahamim and artist Linn Fischer